Despite the cholera-related deaths ravaging Plateau State, the government’s spending priorities remain questionable. While citizens face deadly outbreaks and inadequate healthcare services, millions of naira are funnelled into luxury cars and residences for the Speaker and Deputy Speaker. In this report, Ekemini Simon exposes the state’s failure to prioritise epidemic preparedness at the primary healthcare level, choosing instead to invest in elite comforts over life-saving healthcare infrastructure.

Emmanuel Dati, a man in his 30s from Tabbat community, set out in August 2021 for a brief trip to Mikang Local Government Area (LGA) to visit family, just a short distance from his home in Langtang North LGA. He thought it would be a routine visit, but the following morning, he woke up feeling nauseous, feverish, and with a slight discomfort in his stomach. Dati shrugged it off, assuming it was just malaria. His plan was to get some drugs from a local patent medicine store later in the day.

But things quickly took a turn for the worse.

Within two hours of that initial uneasy feeling, Dati was doubled over in pain, vomiting and experiencing severe bouts of watery stool. His family feared he was infected with cholera. The disease had already begun spreading across the state, and his symptoms aligned with the telltale signs of the waterborne infection: diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration. Cholera, as the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) warns, can be deadly within hours if left untreated.

Realising the urgency of his situation, his family rushed him to the nearest Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC) in Pangkai, Mikang LGA only to find it empty. There were no health workers, and the facility had long run out of basic drugs, vaccines, and consumables.

Waiting would have been futile. A motorcyclist agreed to take him to a General Hospital in Langtang North LGA, but the journey was far from smooth.

“I had no choice but to make the tough decision to travel to another LGA for treatment,” Dati explained, his voice heavy with the memory of that day.

“I was a mess—stooling, vomiting, weak—and the motorcyclist had to stop several times along the way. A 30-minute ride dragged into over an hour.”

By the time they reached the hospital, Dati was gasping for breath. He was diagnosed with cholera and immediately admitted. After a week of intensive care, he finally recovered.

A visit to the Pangkai PHC in July by SolaceBase revealed that not much had changed. Cholera vaccines used in prevention and oral rehydration therapy (ORT) among other antibiotics used in treatment were still unavailable, and despite having solar power installed through the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund (BHCPF), the facility lacked refrigerators for storing vaccines. During the height of the cholera outbreak, health workers had no choice but to rely on antibiotics and Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS), which patients had to procure themselves, while referring critical cases to other hospitals including the General Hospital in Langtang North.

Despite surviving his ordeal, Dati’s story is just one of many in Plateau State, where outbreaks of epidemics including cholera have claimed numerous lives due to a healthcare system that continues to fail its most vulnerable and a government seemingly more focused on luxury spending than epidemic preparedness.

Residents rely on private healthcare, self medication due to poor PHCs’ condition

Not a few local government areas bear witness to the inadequacies of Plateau’s healthcare system. In Rikkos, Jos North LGA, residents faced a similar dilemma during the cholera outbreak. With no vaccines and ORT available at the local PHC, many residents chose not to risk their lives by seeking treatment there. Instead, they turned to private hospitals or relied on herbal remedies to manage the illness.

At the Yar-Kasuwa PHC in Rikkos, the situation mirrored that of Pangkai. While a refrigerator was available, it couldn’t be used as the facility had no power supply, neither electricity nor solar. One staff member, speaking on condition of anonymity, admitted that the facility had never been supplied with cholera vaccines among other drugs used for the treatment of cholera, even during the 2021 outbreak.

“We don’t do much here,” the staff member revealed. “If we have a serious case, we give referrals to a higher facility. Most of what we do here is antenatal and a few other services.”

On vaccination days for pregnant women and children, the staff explained, they are forced to go to the local government headquarters to collect the vaccines, as there are no proper storage facilities at the PHC.

In the absence of public healthcare options, private clinics have become lifelines. At Jama’a Nursing Home, a private clinic in Rikkos, Dr. Zakari Alkali confirmed that his clinic treated 15 cholera patients in 2023 alone. But with private healthcare comes high costs, a burden that many residents can barely afford, leaving them vulnerable to further outbreaks in a region already struggling with inadequate healthcare infrastructure.

Dr. Zakari Alkali noted that the consistent inflow of patients to his private clinic is largely due to one critical factor: availability. With a functional refrigerator, steady electricity, and solar power, his facility can store and preserve essential vaccines and drugs, including those for cholera. Yet, even with these advantages, Alkali expressed concerns. “The drugs are not enough,” he said, explaining that he has to prioriti2e those in the most critical conditions due to limited supplies.

Another challenge, Alkali noted, is the declining trust in orthodox healthcare. “Many people in the community resort to self-medication, waiting until their situation worsens before coming to the clinic,” he lamented.

One such case is Blessing Timbyen, a survivor of cholera, who initially opted for self-medication after losing faith in her local PHC. Reflecting on her experience, she said, “After a community festival, I started stooling at night, but the vomiting didn’t start until the next day. By then, I was too weak to even vomit properly. I didn’t bother going to the health centre. My father gave me a local concoction mixed with kunu, and I drank it for the whole day.”

While Timbyen’s condition persisted for five days, the combination of local remedies and antibiotics eventually helped her recover. However, this practice comes with risks, as the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) has repeatedly warned against the dangers of self-medication.

Another survivor, Magdalene Tyem from Jivir community in Pankshin LGA, recalled her narrow escape from death during the 2021 cholera outbreak. “I woke up with a stomach upset around 3 a.m., and I couldn’t stop going to the toilet. By morning, I was vomiting, and my body felt completely drained,” Tyem said. Despite being taken to the Jivir PHC, she found no healthcare provider on duty.

“I had vomited and stooled out everything in me. I thought I was going to die,” she recalled.

Her family eventually took her to a local patent medicine shop, where she received saline drips daily for a week before she regained her strength.

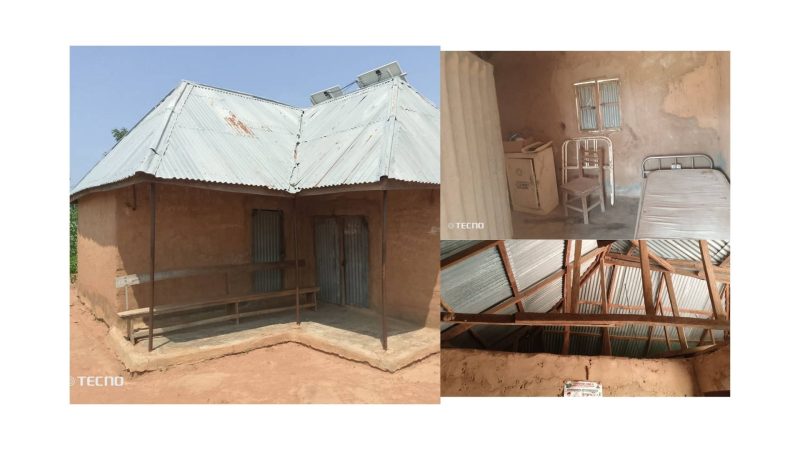

A visit to the Jivir PHC in August by this reporter revealed a facility in dire straits. The building is dilapidated, with a leaky roof, no electricity, solar power, or refrigeration. Basic medical equipment like laboratory tools and drug storage facilities are absent. Worse still, the centre is staffed entirely by volunteers. One of the volunteers, who spoke anonymously, confirmed that the PHC hadn’t received cholera vaccines among other cholera medications in over five years.

“We can only provide first aid here and that is saline infusions that the patients have to pay for. Once they’re stable, we refer them to the General Hospital in Langtang North, which is about 65 kilometers away,” she explained.

Cholera continues to claim lives in Plateau

Dati, Timbyen, and Tyem, who recounted their close encounters during the 2021 cholera outbreak, were among the lucky ones who survived. However, 21 other residents were not as fortunate, according to the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), though the Plateau State Government recorded an even higher toll of 28 deaths. The entire state, spanning 17 local government areas, was affected, with 1,490 cases reported that year.

In 2022, a brief reprieve came with 39 reported cases and one death, though the state capital, Jos North, remained vulnerable, recording over 20 cases in the first four months. Last year, Plateau State continued to grapple with cholera, although reported cases were fewer, with NCDC documenting 15 instances.

Yet, behind these numbers lies a tragic reality: the slow response to cholera, compounded by inadequate vaccines, a lack of medical consumables, and infrastructure issues like the absence of refrigerators and reliable electricity to store vaccines, all contributed to these preventable deaths. The shortage of healthcare providers only deepened the crisis.

The NCDC recommends that Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs) serve as the first point of care for cholera patients showing early symptoms. But the condition of PHCs in Plateau State raises doubts about their reliability for treating cholera effectively.

According to the minimum standards set by the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHCDA), each PHC is required to have cholera medications, a connection to the national grid or alternative power sources, and at least one refrigerator for storing vaccines. However, the PHCs visited during this report lacked these essential facilities, making it nearly impossible to administer effective treatment to cholera patients, among other healthcare challenges.

Additionally, the NPHCDA standard calls for each PHC to be staffed with 19 healthcare personnel and 5 supporting staff, making a total of 24. Yet, none of the visited PHCs had even five personnel on duty—many were operated solely by volunteers.

Dr. Raymond Juryit, the Executive Secretary of the Plateau State Primary Healthcare Development Board (PSPHCDB), admitted the alarming state of staff depletion across the state’s 1,200 PHCs. He revealed that the staff strength had plummeted from 14,000 in 2016 to fewer than 3,000 in 2024, with many of those remaining being volunteers.

More concerns over Plateau Government investment in primary healthcare

The deplorable condition of these medical facilities is not coincidental. It mirrors the Plateau State government’s misplaced spending priorities when it comes to investing in primary healthcare and, more importantly, the minimal value placed on the lives of ordinary citizens.

During the cholera outbreak in 2021, findings revealed that the state government relied heavily on the Federal Government for vaccine supplies. Then-Commissioner for Health, Dr. Nimkong Lar, confirmed that the Federal Government had supplied 105,600 doses of cholera vaccines to the state. However, health workers at the PHCs visited stated that the vaccines never made it to their facilities. Colleagues at other facilities corroborated this claim, noting that the vaccines were insufficient and only administered at hospitals. Despite PHCs being the first point of care for most citizens, the state government failed to procure its own vaccines and also failed to make available to PHCs relevant drugs needed for the treatment of cholera.

Plateau Government fails in preparedness for another outbreak

These gaps in healthcare infrastructure and availability of medicines are no secret. A closer look at the Plateau State government’s Appropriation Laws reveals clear awareness of the medical deficiencies plaguing its primary healthcare centres. Yet, despite this, a lack of political will and misplaced budgetary priorities continue to undermine critical healthcare services.

In the wake of the 2021 cholera outbreak, one would anticipate a proactive response to bolster healthcare readiness. However, the 2022 fiscal year saw no budgetary allocations for essential healthcare items such as drugs, clinic consumables, or necessary equipment. Adding to the concern, the Audited Financial Statements of 2022 show that the Plateau State Primary Healthcare Development Agency (PSPHDA) received no release of funds for its overhead costs, despite a modest approved budget of N200,000 while the government spent N23.6m on renovating the Speaker’s Guest House. This absence of funding meant that no money was allocated for the day-to-day operations of the primary healthcare centres across the state.

By 2023, the state budget did include provisions for medical supplies and infrastructure improvements. The sum of N50 million was allocated for drugs and clinic supplies, another N50 million for freezers, and N35 million for solar energy to power primary healthcare centres. However, none of these funds were released, according to the Plateau State Audited Financial Statements of 2023. This continued neglect has left critical healthcare facilities in disrepair and lacking essential resources.

Plateau Government spends millions on Assembly cars and Speaker residences while healthcare suffers

The Plateau State Government has attributed the poor condition of primary healthcare centres (PHCs) in the state to a lack of funds and insufficient prioritisation by previous administrations.

Dr. Raymond Juryit, the Executive Secretary of the Primary Healthcare Board, emphasised that financial constraints have been a major factor contributing to the deteriorating state of PHCs.

“It is true that most health facilities are not in good shape,” Dr. Juryit explained. “But PHCs are the responsibility of both the State and LGAs. Sixty percent of the funding should come from the LGAs, and 40 percent from the State. Unfortunately, the LGAs have not been living up to their responsibility. For us to address these gaps, the LGAs need to contribute.”

Dr. Juryit also noted that Governor Caleb Mutfwang’s administration, which began in May 2023, has made strides in revitalising the sector by renovating six PHCs. “The sector has been neglected for quite some time. But this administration has shown it is ready to turn things around. If past governments had done what the current Governor is doing, there would have been significant improvement in healthcare service delivery at the primary level.”

However, this defense of the local governments’ failure to provide 60 percent of the funding is questionable. Until a recent Supreme Court ruling that granted local government autonomy, local government revenues were controlled by the state government through the State Joint Local Government Account, raising doubts about where the real accountability lies.

While the Plateau State Government attributes the poor state of primary healthcare centres (PHCs) to a lack of funds, evidence suggests that the issue lies more in spending priorities rather than actual financial constraints.

Contrary to the Executive Secretary’s assertion that financial shortages hindered the improvement of PHCs, investigations by SOLACEBASE revealed that the real issue lies in spending priorities, not a lack of funds.

Despite two consecutive years of cholera outbreaks, the Plateau State Government allocated significant resources to less critical areas. Instead of investing in critical healthcare needs, analysis of the 2023 Audited Financial Statements showed that the government carried out an extrabudgetary spending of N2.055bn on “1 No Toyota Land Cruiser Jeep 2.7 Prado TXL.”

Extrabudgetary spending refers to expenses made outside the approved budget, often bypassing established financial plans and priorities. In this case, the vehicle was neither approved nor included in the budget. The only luxury jeeps approved for the State House of Assembly were 12 Hilux 4WD vehicles, with an allocated budget of N1.1bn.

Even more surprising, the State Assembly, which had N285m approved for the Procurement of 9 No. Toyota Corolla 2.5 LE, ended up spending a staggering N1.03bn on these vehicles resulting in discretionary spending of N745m. This implies that each vehicle was bought at an inflated cost of N114.4 million. Such significant off-budget expenditures on luxury vehicles could have been better allocated to strengthening the primary healthcare system by acquiring much-needed medications, consumables, and essential medical infrastructure to mitigate future epidemics.

Even more troubling, the government disbursed N649.8m for the construction of residences for the Speaker and Deputy Speaker, further diverting critical funds away from healthcare. Meanwhile, the Plateau State Primary Healthcare Development Agency received a meagre N22.18m out of the N250.2m budgeted for its overhead costs which translates to 8.9 percent of the approved funds.

These decisions reflect a glaring neglect of healthcare, with devastating consequences for the state’s most vulnerable populations.

Mutfwang’s government promises revamp of Primary Health Care

Reacting to findings of this report, Dr. Juryit, emphasised that the current administration of Governor Caleb Mutfwang’s is actively addressing the critical needs of primary healthcare in the state. According to him, by the end of the 2024 fiscal year, the administration plans to revitalise 127 health facilities: five under the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), six from the state’s budget, and 116 through a World Bank loan secured by the government. The overarching goal is to have one functional health facility in each ward by 2025.

The Executive Secretary said with the local government autonomy, the local government Councils in a committee with relevant stakeholders have agreed to contribute 60 percent of needed funding to the primary healthcare board while the State has committed to its 40 percent. If the recommendations from these committees are implemented, Dr. Juryit said that the state could employ an additional 4,774 healthcare professionals, including doctors, nurses, midwives, and Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs).

Addressing the energy needs of PHCs, Dr. Juryit shared that the state government has secured a partnership with the European Union, which will soon assess the facilities and provide solar energy solutions. He also clarified that while the provision of cholera vaccines is not currently a priority for the state government, its focus is on cholera prevention through improved healthcare infrastructure and services.

However, upon closer examination of the 2024 Approved Budget for Plateau State, no allocation was found for the revitalisation of primary healthcare centers (PHCs). This discrepancy raises questions about the legal and financial framework supporting the proposed revitalisation of 127 health facilities within the fiscal year, particularly given the absence of a supplementary budget.

Repeated attempts to seek clarification from the Executive Secretary, Dr. Juryit, were met with silence. Despite confirmation that a WhatsApp message sent to him on September 17 seeking clarification was read, he did not respond to inquiries. Multiple follow-up calls, texts, and WhatsApp messages were sent throughout the day on September 18, but no response was received.

Experts question Plateau state’s long-term strategy

While Dr. Juryit, Executive Secretary of the Primary Healthcare Board, expresses optimism about the administration’s plans, public health experts are raising concerns about the viability of the state’s approach.

A healthcare policy analyst, Koko Udo of Bestway Initiative for Health, Education and Self-sufficiency cautioned that without consistent funding and political commitment, the ambitious plan to revitalise 127 health facilities in less than four months to the end of the 2024 fiscal year, including those supported by the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), the state, and the World Bank loan, may face delays or fall short of expectations. He said if the government must record success, it must reconsider its timeline, provide comprehensive information for public monitoring by Civil Society organizations and citizens, and strictly adhere to public procurement laws to ensure value for money.

Dr. Laz Eze, CEO of Talk Health9ja and founder of the “Make Our Hospital Work Campaign,” has raised concerns about Plateau State’s decision to deprioritise cholera vaccines among its prevention strategies. With years of experience managing cholera outbreaks, Dr. Eze emphasised that while safe drinking water is crucial for cholera prevention, vaccines play a vital role in preventing diseases. He urged the government to clarify its prevention approach and explain why cholera vaccines are not a priority.

In addition, Olusegun Elemo, Executive Director of the Paradigm Leadership Support Initiative, criticised the Plateau State Government for its heavy reliance on loans to finance health sector development. Elemo argued that while borrowing for development is not inherently problematic, the loans must be sustainable and aligned with the state’s revenue generation capacity. He stressed that such debt obligations should be directed towards development priorities and managed efficiently.

This SolaceBase publication is produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development, Inclusion and Accountability Project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation.