In Dungundun, Umaru’s community in Sule-Tankarkar local government area in Jigawa State, there is no hospital. So, he rushed them to the Danladi Basic Health Clinic, located in Danladi, another community in Sule-Tankarkar.

The Danladi Basic Health Clinic, where residents of Dungundun have had to seek care over the years, lacks the facilities to treat outbreaks like meningitis. It only handles antenatal care, immunisation, family planning, child survival, nutrition, health education, and community mobilisation.

Umaru’s children didn’t make it to Gumel General Hospital. They died on the way.

“On our way to Gumel, my two sons became weak and started vomiting too, they both died and we turned back home and buried their remains, “Umaru said, sitting in front of his house.

“It was a terrible experience for me and my family because we did not see their death coming. “Four other children died the same day and we buried them.”

Jigawa, the epicentre of Meningitis outbreak

Meningitis is a highly infectious disease that can be fatal if left untreated. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), up to 50 percent of people infected with meningitis may die if they do not receive treatment. Even when treated, 10 to 20 percent of survivors will experience long-term effects, such as deafness, blindness, or limb loss.

Meningitis is spread through direct contact with droplets from the nose and throat of an infected person. Close and prolonged contact, such as sneezing and coughing, smoking, and overcrowding, can increase the risk of transmission.

In an interview with SOLACEBASE, Dr. Francis Fagbule, a public health expert at the University College Hospital in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria, explains that the dry season, which is characterised by dry and dusty harmattan winds in Northern Nigeria, also facilitates the spread of meningitis-causing germs.

The situation gets worse when most of the population in the affected States live in poorly ventilated, over-crowded rooms where the internal room temperature could rise above 45°C during daylight hours.

Common symptoms include fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, neck stiffness, and altered consciousness levels. In younger children, these symptoms may be more difficult to detect. Between 1 October 2022 and 30 April 2023, 176 deaths were recorded out of 270 confirmed cases of Meningitis in Nigeria. Out of this number, Jigawa state alone accounted for 233 confirmed cases and 65 deaths. In February, 38 deaths were recorded across seven local governments in the state.

Fareedah Munir, a senior scientific officer at the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), told SOLACEBASE that the magnitude of the meningitis outbreak in Jigawa was not surprising, given that it borders the Zinder region in Niger Republic, which has experienced a protracted meningitis outbreak and reported cases in 2022. The first case was reported from Garin Mu’azu in Sule Tankankar.

By July 2, 2023, Jigawa state had recorded 66 deaths, mostly children, from 234 confirmed cases of meningitis, with 22 of the 27 local government areas reporting cases.

With no facility, it was a harvest of deaths

Umaru’s two children are among a long list of children and adults who died, following the outbreak of Meningitis in Jigawa State due to a lack of access to healthcare. A World Health Organization (WHO) report showed that Sule-tankarkar was among the epicenters of the outbreak, having crossed the epidemic threshold of 10 suspected cases per 100,000 population.

Dungundun, the hardest-hit community, witnessed the tragic loss of at least 50 lives. The relentless frequency of deaths deterred many from visiting the community. Abdullahi Alhassan, a resident, expressed the prevailing sense of abandonment, revealing that they were recording seven to eight deaths every week.

Abdullahi Alhasan says several promises had been made by the government to improve healthcare.

The community’s remote location and poor roads compounded the problem, causing children to succumb to illness before reaching a hospital.

Even when they managed to reach a hospital, overcrowding often hindered prompt care. Dr. Fagbule explained that limited access to healthcare facilities, diagnostics, and treatment options, particularly in rural areas, delayed the disease’s detection and management.

Ali Hassan, a community leader, recalled a past promise from the administration of Badaru Abubakar to provide a healthcare facility before the outbreak, a promise left unfulfilled. He remains hopeful that the current administration will address this urgent need, preventing further loss of lives.

“Till now, we have not heard from the government in terms of providing us with a healthcare centre, but we hope that the current administration will look into it so we don’t all lose our lives.”

Meningitis Outbreaks: A recurring challenge in Nigeria

Over the past three decades, Nigeria has grappled with recurring epidemics of Cerebrospinal Meningitis (CSM), a disease prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa. Notably, these outbreaks struck in 1970, 1975, 1977, 1986, and 1996, with the latter being the most severe.

In 1996, Nigeria faced a formidable crisis as it recorded a staggering 109,580 cases of CSM and a tragic toll of 11,717 lives lost. This alarming outbreak primarily affected states situated in the African meningitis belt, including Katsina, Sokoto, Kebbi, Kano, Niger, Kaduna, Jigawa, Bauchi, Yobe, and Borno. Cases also emerged in states located just beyond this belt, such as Adamawa, Taraba, Plateau, and Kwara. Even regions as far south as Ogun, Delta, Cross River, and Enugu reported cases.

Amid this dire situation, a massive vaccination campaign was launched, orchestrated by the Federal Task Force. This concerted effort, in collaboration with organisations such as the WHO, MSF, the Red Cross, and state and local governments, swiftly addressed the crisis. Immediate attention was directed to the most affected states, namely Kano, Katsina, and Bauchi, marking a pivotal moment in Nigeria’s battle against CSM.

Existing, dilapidated and non-functional

However, despite these commendable efforts, a haunting reality persists in Nigeria’s healthcare landscape. Rampant issues of existing, dilapidated, and non-functional medical facilities have left countless families in distress. Mohammed Kabir, who tragically lost his daughter Nana Ziyada to the outbreak due to a lack of accessible care in Mele, another local government in Jigawa State, embodies this heart-wrenching struggle. Now, he grapples with the loss of his beloved daughter, left with three surviving children and the weight of an unforgiving healthcare system.

Muhammad Kabir

Ziyada’s story is a tragic example of the healthcare challenges faced by communities like Mele. A lack of functional healthcare centers leaves families helpless in times of need. Babande Abdulrahman’s account echoes this struggle, as he tried to save his 8-year-old daughter with local herbs due to the absence of proper medical care.

Babande Abdulrahman lost his 8-year-old daughter to the outbreak

The grim reality of inadequate healthcare facilities is exemplified by the deteriorating state of Mele’s lone health center, a dilapidated structure with leaky roofs, broken ceilings, and cobweb-covered corners.

Dilapidated PHC in Mele

Community members describe the facility as virtually useless, with an absentee staff member and no access to essential medications. Residents are forced to embark on an 18 km journey to Gumel General Hospital in times of emergencies, often arriving too late to prevent tragic outcomes. Nigeria’s healthcare system is at a crossroads, where commendable efforts to combat outbreaks are stifled by crumbling infrastructure, leaving families to bear the devastating consequences.

Yusuf Ahmad, the head of Mele, grimly revealed that more than 50 lives, spanning children and adults, succumbed to the outbreak since 2022, designating the community as yet another epicenter of this devastating crisis.

However, other community leaders assert that the toll surpasses 80 lives. When combined, these harrowing figures surpass the 100 mark, reflecting the tragic loss experienced by two closely-knit communities.

Yusuf Ahmad, Village head of Mele says over 50 lives were lost to the outbreak.

Ahmad passionately underscores that this staggering loss could have been mitigated had the community possessed a functional healthcare center, providing swift access to critical care. He implores both state and federal authorities to intervene urgently, providing a well-equipped health center staffed with professionals ready to attend to the community’s medical needs. He emphasises that the ongoing loss of young lives during outbreaks is a burden too heavy to bear.

Mele PHC under lock and key

Mele’s plight extends beyond the immediate loss of lives. Surviving children bear the scars of the outbreak, with some experiencing severe neurological damage, marked by erratic behavior and attempts to escape. Others grapple with hearing impairments and visual challenges. The aftermath of the outbreak continues to cast a long shadow over the community’s future.

Vaccine inadequacy is a major challenge

Early diagnosis and treatment, appropriate case management, active community-based case-finding, and reactive mass vaccination of affected populations are critical in managing the Meningitis outbreak.

Sadly, inadequate vaccination coverage remains a major challenge in Jigawa State which is one of three states where over 600,000 children are yet to be vaccinated against childhood killer diseases, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

For instance, a six-day reactive immunisation campaign by the Jigawa State government, in collaboration with the NCDC, the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency, (NPCPDA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2023, only targeted 194 486 people aged 1-29 for vaccination with multivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccines in 17 wards that exceeded the epidemic threshold.

Munir told SOLACEBASE that while the reactive vaccination targeted campaign was successful, other wards that were not vaccinated due to low cases at the time of the campaign, later passed the threshold – the number of suspected cases above which a disease requires an urgent response – which prolonged the outbreak.

The doctor said that the vaccine, Meningococcal conjugate needed to stop the outbreak in Jigawa is not readily available. She said that a detailed request through NPHCDA was sent to the International Coordinating Group (ICG) which manages and coordinates the provision of emergency vaccine supplies and antibiotics to countries during major outbreaks.

“But the ICG only provides vaccines to specific wards when a certain threshold is passed, “she said, adding that the Jigawa state government also responded late to the outbreak.”

In addition to vaccine shortages, a health expert in the state, Muhammad Tukur said poor immunisation compliance and a lack of information and awareness are also contributing to the outbreak.

In remote villages, people don’t often know where to go or what to do if they experience symptoms of the disease. There is also a shortage of healthcare workers in these areas, and the disease can be misdiagnosed.

“The disease shares similar symptoms with other diseases and so, we have had cases where individuals are given different treatments at local hospitals. But we don’t just jump into conclusions because the disease requires investigation to confirm its existence.”

He, however, said that the current administration has shown better commitment to tackling the outbreak by increasing collaboration with community-based organizations and traditional rulers to keep the people informed as well as providing necessary support to enable workers get to the villages

“The government said that it plans to recruit more workers and also confirm the casual workers to help deal with the challenge of lack of enough personnel, hopefully, that will be done soon,” he said.

Poor funding for healthcare

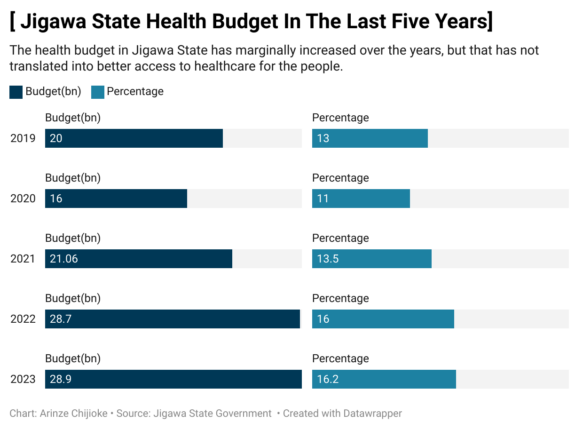

An examination of the budget performance in Jigawa reveals a stark reality: the previous administration under Abubakar Badaru did not place the well-being of communities at the forefront of its priorities.

Not only was there a glaring absence of dedicated allocations for epidemic preparedness—critical for equipping the state to anticipate, prevent, identify, and manage disease outbreaks—but there was also a glaring oversight in addressing the unique healthcare needs of the very communities ravaged by the outbreak.

It’s akin to embarking on a challenging journey without a map or compass, leaving communities vulnerable to the relentless storm of disease without adequate defenses.

Although Gov. Badaru announced an allocation of 16 per cent, amounting to N28.7bn of the 2022 Jigawa State budget, which stood at N177.7bn, to the health sector, findings show that the actual expenditure falls short of this commitment.

Jigawa budget

A closer look reveals significant discrepancies. For example, out of the N2,171,200,000 earmarked for the Primary Health Care Development Agency in 2022, only N1,286,573,049.91, equivalent to 59.3%, was actually released. A breakdown of the performance reveals that no funds were released during the first quarter, with only N236,598,329 disbursed in the second quarter, a mere N29,300,009 in the third quarter, and a substantial N1,020,674,711.91 in the fourth quarter. Of the N9,386,500,000.00 allocated for hospital and health center construction in 2022, only N3,692,706,206.36 was released, accounting for just 39.3% of the total budget.

Despite a substantial budget allocation of N4,062,000,000.00 for the Primary Health Care Development Agency (PHCDA) in 2023, the first quarter saw a meager release of only N89 million (N89,658,967.04), constituting a mere 2.2% of the total budget. In the second quarter, the release increased significantly to N908 million (N908,051,404.64), bringing the cumulative sum to N997,710,371.68, equivalent to 24.6% of the total budget.

This substantial shortfall between budgeted and released funds raises concerns about the adequacy of financial resources allocated to the healthcare sector.

In a research on African health financing, Dr. Nkechi Olalere from Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Center (SPARC) and a health financing professional, Agnes Gatome-Munyua emphasise that despite commitments to universal health coverage, governments lag in health funding. Low budget execution and wastefulness strain resources, forcing citizens into high out-of-pocket expenses and creating an inequitable healthcare system favoring those who can pay.

The 15 per cent Abuja declaration is still a far cry

In April 2001, African Union member states met in Abuja where they committed to allocating 15% of their government budgets to health. Sadly, research has shown that although many African countries have marginally increased health spending overall, only a handful of countries have met this target in any given year, with only two in 2018.

Back in Nigeria, research by ONE Campaign- Titled Post-Pandemic Health Financing by State Governments in Nigeria 2020 to 2022 – showed that only Kaduna and Sokoto have consistently hit the required threshold of 15 per cent between 2020 and 2022 and that sub-national governments’ persistent under-allocation of resources to the health sector has led to a funding gap of N1.36 trillion between 2020 and 2022 alone.

National budget

On the federal level, the Nigerian government’s budget allocation to the health sector has averaged a modest 4.7% over the past two decades. The highest allocation, 6.1%, was seen in 2012. However, in 2023, there was a historic allocation of over a trillion Naira (N1.17 trillion) to the sector, marking a significant milestone.

Although the figure was a significant increase from the N547 billion allocated in 2021 and N826.9 billion allocated to the health sector in 2022, it only represents 5.75% of the total budget and a little above one-third of the 15% agreed at the declaration.

A Budgit research shows that if funding for the health sector is not adequately prioritised from the approved budget, (with about 15 per cent of total allocation), any subsequent reductions during disbursements due to reduced revenue inflows could mean that health spending needed to create the desired impact would be considerably smaller in states.

Health ministry refuses to provide details on outbreak

In order to get the Jigawa State Ministry of Health to respond to questions concerning efforts made to tackle the outbreak of Meningitis in the state, including specific spendings on epidemic preparedness and vaccines, this reporter called both the Secretary of the Jigawa State Primary Healthcare Development Agency, Dr Kabiru Ibrahim on September 7 and the State Epidemiologist, Samaila Mamuda on Tuesday, September 12.

While both officials insisted that this reporter travel down to the Ministry to seek permission from the commissioner, the state epidemiologist said that it was wrong to visit any location without first seeking approval.

“It is an offence for you to just come into the state without following protocol,” he said. The state cannot deny you data but that is the protocol all over the country.”

However, there is no law in Jigawa State or Nigeria that requires a journalist to seek permission from the government before embarking on a story.

Subsequently, a Freedom of Information request (FOI) on percentage releases on primary healthcare, amount appropriated and spent on epidemic preparedness from 2016 to 2022 was submitted to the Jigawa State Ministry of Health on Friday, October 13. At the expiration of seven days stipulated in the FOI Act of 2011 on Tuesday, 24 October, no response was received.

Finding solutions

In their research, Olalere and Gatome-Munyua, emphasised that increasing prioritisation of the health sector and boosting health expenditure are the most practical methods for enhancing healthcare resources. They urged governments to transition from mere spending targets to a more critical evaluation of what level of resourcing can truly enhance population health and promote universal health coverage (UHC). This includes assessing the optimal utilisation of funds to advance public health and identifying opportunities to enhance efficiency and reduce resource leakages.

Furthermore, they stressed that health ministries should actively advocate for sufficient resourcing, presenting compelling arguments for investing in health as a sector that fosters human capital development, poverty reduction, equity, pandemic preparedness, increased workforce productivity, and employment opportunities.

Fagbule emphasised a multifaceted strategy for preventing and managing Meningitis. This includes early detection and surveillance, raising public awareness through education about meningitis symptoms, promoting prevention through vaccination, and encouraging prompt medical care-seeking behavior.

He further stressed the importance of improving access to healthcare facilities and ensuring the availability of diagnostics and treatments for individuals affected by meningitis.

This SOLACEBASE publication is produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the collaborative Media Engagement for Development, Inclusion, and Accountability Project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation.