Lagos roads had woken up, and Second Rainbow was no exception.

Traders flung the gates of their shops open. Others who had no shops took over the street corners under umbrellas, with wares sprawled in front of them.

It was a regular day in Lagos, the city that never sleeps and where people sold everything to make ends meet.

“Festac, Festac,” motorcycle drivers popularly called okada riders, called on to passers-by.

It was their way of getting customers. Under the bridge in Second Rainbow, shuttle buses and motorcycle drivers sat in their yellow and black painted vehicles, waiting for their turn.

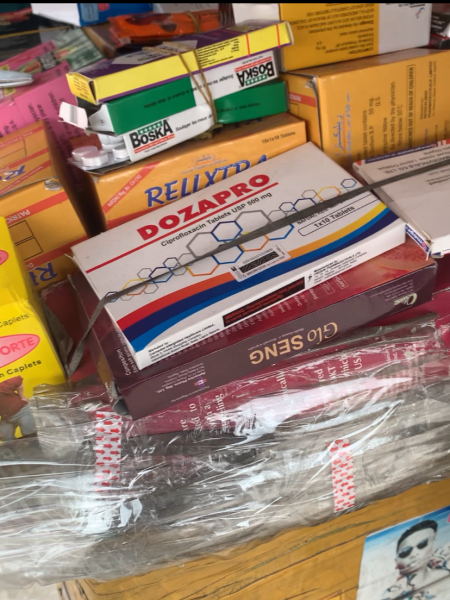

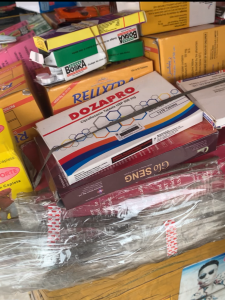

Sitting on stools across an NNPC filling station were traders. Among them was a young man who appeared to be in his early twenties and wore a green shirt with a pair of black shorts. In front of him was a basket where he displayed packs of medicine.

FIJ’s reporter asked for Flagyl and Paracetamol. He brought out a pack of Emzor Paracetamol and a pack of medicine with “Unigyl” written on it and handed one of each to her.

As he closed the packs and returned them, I asked if they were original.

“It is original,” he replied, without looking up from what he was doing.

This young man, whose identity is unknown, is one of Lagos’s many roadside medicine vendors. He arrives at that location by 8 am every morning and carts them away by 10 pm every night.

This was his bread and butter.

Such sights are common in Lagos and some other parts of Nigeria.

A THRIVING BUSINESS

In many corners across various Lagos communities, many sell medicines in baskets or bowls perched on their heads.

According to Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of the World Health Organisation (WHO), health is a fundamental human right. Everyone should enjoy good health regardless of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.

This right, however, has gradually become a privilege that only the rich and the middle class residing in urban and semi-urban communities can access.

Only a minority can boast of access to healthcare in Nigeria. Although there is an absence of current statistics on the population of Nigerians who lack access to healthcare, the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHCDA) claims that six in 10 Nigerians lack access to healthcare.

This population consists of people who reside in rural areas with low incomes. They are forced to rely on patent medicine vendors, sometimes casually called chemists, for their healthcare needs. These chemist shops sell over-the-counter medicines.

These patent medicine vendors are registered and belong to associations such as the Lagos State Medicine Dealers Association (LSMDA) for vendors operating in Lagos or the Nigerian Association of Patent and Proprietary Medicine Dealers (NAPPMED), the national association for medicine vendors.

However, another crop of vendors in Nigeria sell their medicine by the roadside or hawk it on the streets, unlike patent medicine vendors who have licences. Unlike LSMDA and NAPPMED members, these roadside medicine vendors are not registered.

READ ALSO: B-GAG HEALTHY MEDICINE Illegal but Marketed in Nigeria

They also do not adhere to guidelines stipulated by the Pharmaceutical Council of Nigeria (PCN) for patent medicine vendors.

The PCN stipulates that patent medicine vendors should receive formal training, meet a minimum age requirement, obtain location approval and provide a reference of good standing before they are given licences to operate.

Catherine Ubani, the public relations officer of the LSMDA, told FIJ on Wednesday that these guidelines were also applicable to medicine vendors in Lagos and that the roadside medicine vendors do not meet the requirements.

“Before you are allowed to become a patent medicine vendor in Lagos or join LSMDA, you must have attained an age of 21, the minimum level of education is the Secondary School Certificate Examination (SSCE), must have undergone an apprenticeship and studied the trade and mastered it,” said Ubani.

“They are also expected to have shops in conducive environments, and those shops must meet certain standards. For instance, they can’t operate their business inside a metal container because it will generate heat, and heat can damage the quality and efficiency of medicine. Medicine has to be stored at room temperature and not exposed to the sun.”

That night, I returned to this trading hot spot and asked for Procold, a drug for cold, headaches, flu and fever. The roadside trader produced a sachet with “Clearcold” inscribed on it. It was a liquid substance inside the sachet.

When I told him this was not Procold, he tried again. Like a magician with his bag of tricks, this trader dipped his hands into the basket and brought out another medicine with red packaging. The new drug had “Petsow Flu” written on it.

That same night, FIJ spotted two roadside medicine vendors at Cele Bus Stop in Lagos. They were going about their medicine business as usual.

THE IMPLICATIONS

While these trades may seem normal, they are far from normal, says Abiodun Abdulazeez, a pharmacist. Habib Yusuf, a member of the Pharmaceutical Council of Nigeria (PCN), shared Abdulazeez’s concerns.

Both pharmacists described the trade as improper because the sale of medicines is regulated to occur only within licensed environments, not by the roadside.

“The sale and distribution of medicines are strictly regulated activities that should only occur within licensed controlled environments,” Yusuf told FIJ.

“It is highly improper and illegal for medicines to be hawked or sold by the roadside. This practice contravenes multiple pharmaceutical and healthcare regulations and poses significant risks to public health.”

While speaking with FIJ on Wednesday, Abdulazeez said the sale of medicines by the roadsides has numerous implications.

According to Abdulazeez, these range from implications that stem from poor storage to the possibility of substandard, expired or unregistered medicines circulation.

“The sale of medicines by the roadsides or the hawking of medicines is wrong. This has numerous implications, beyond what one can imagine,” Abdulazeez told FIJ.

“Poor storage management could lead to low efficacy when drugs are taken subsequently leading to poor therapeutic outcomes. Dosage verification is another area where vendors can fail in their duty in the sense that it is only trained personnel who can recommend dosage without errors, either underdose or overdose.

“It is easy for these people to be approached by producers of substandard medicine for the purpose of business, including the sales of expired medicines which are dangerous for consumption.”

Ubani, the LSMDA PRO, shares the same sentiments.

She told FIJ that members of the LSMDA have a list of medicines they are licensed to sell, including over-the-counter medicines, and their activities are regulated. Still, the activities of these roadside medicine vendors are unregulated, and they can engage in the sale of substandard medicines or illicit substances.

“They sell all kinds of drugs. Those of us in the association have an approved list of drugs we can sell and can only sell over-the-counter drugs. But these people, there is no type of medicine that you cannot get from them. The fact that their shop is mobile means they can always get away with this,” said Ubani.

She added that they may claim to purchase their medicines from trusted pharmacies, but this may not always be the case as there were open markets where medicines were sold and they could get them from these markets.

Habib added that this trade is characterised by the absence of transparency which creates an environment for the proliferation of substandard, counterfeit and expired products.

“Licensed sellers are subject to regular inspectors and quality checks which help maintain the integrity and efficacy of the medications they dispense. This system helps prevent the distribution of substandard, counterfeit or expired drugs which can pose serious health risks for consumers,” he told FIJ.

“For informal sellers, the supply chain is often opaque and unverified. The lack of transparency creates an environment for the proliferation of counterfeit, substandard or expired medications.”

For decades, Nigeria has been at war with substandard medicines. Dora Akunyili, the former Director General of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), waged a war on the circulation of substandard and unregistered medicines in Nigeria before her death. Years later, this issue has reemerged.

In September, NAFDAC alerted Nigerians about the circulation of multiple substandard drugs. These roadside vendors pave the way for the circulation of these substandard medicines as their activities are unregulated. The consequences of this are rife and range from worsened medical conditions to death.

JUST PAINKILLERS

Aside from these roadside medicine vendors, there is another group of people who sell medicines without a licence. They too do not belong to associations like the LSMDA or NAPPMED.

These are vendors who sell consumables alongside painkillers such as Paracetamol or Panadol. They are very common in some communities in Lagos, including Festac and the Isawo axis of Ikorodu.

On November 6, FIJ went around some closes in 512 Road and 23 Road and inquired from some vendors who sold at the gates if they had paracetamol. These sellers are popularly referred to as mallam or aboki by Festac residents.

One of them, who had a shop close to Ituah Hospital on 512 Road, was lying on a bench when I spotted him. I asked if he had Paracetamol and he went into his shop, brought out a small transparent bowl where he kept sachets of Paracetamol and handed me one.

When I asked if he checked the NAFDAC numbers on the medicine he sold, he nodded.

“Yes. They are original. I check if they have NAFDAC numbers,” he said.

The trader whose shop is by the gate in 23 Road, P Close, responded similarly when FIJ asked the same question. He told FIJ that he purchased his medicines from a trusted place and they were authentic for this reason.

Abdulazeez, the pharmacist, opined that there was nothing wrong with these people selling painkillers.

“They are meant to fill the vacuum in areas where medicines are not easily accessible,” he said.

Akinbolu Akinniyi, a Festac resident, told FIJ that he has never purchased medicine from these traders or those who sold by the roadside because he was concerned about the authenticity of the medicine they sold.

“No, I’ve never patronised them and have never considered it. As much as some people might have made a purchase from them, I don’t trust the authenticity of the medicines,” said Akinniyi.

A REMEDY

Habib proffered some solutions to this trade which poses a significant threat to the health of millions of Nigerians.

He recommended public enlightenment on the dangers of patronising these vendors and called for the implementation of stricter laws regulating those who can dispense medications.

Habib added that the government should improve access to health care as the lack of access to quality and affordable health care is one of the factors driving many Nigerians to patronise roadside medicine sellers.

This story was produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development Inclusivity and Accountability Project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation.