In Qur’anic schools across Bauchi, Almajiri children suffer abuse and exploitation at the hands of their teachers, yet the government fails to provide any protection despite the existence of state laws, WikkiTimes’ investigation reveals.

SEPARATED by a distance of approximately 110 kilometers, three individuals—Musa Abdullahi (16), Usman Musa (15), and Abubakar Garin-Dawa (17)—find themselves bound by a shared destiny marked by suffering and sorrow. These young Almajiri children have become unwilling victims of child labour within the Tsangaya school overseen by Alarama Idi Yusha’u.

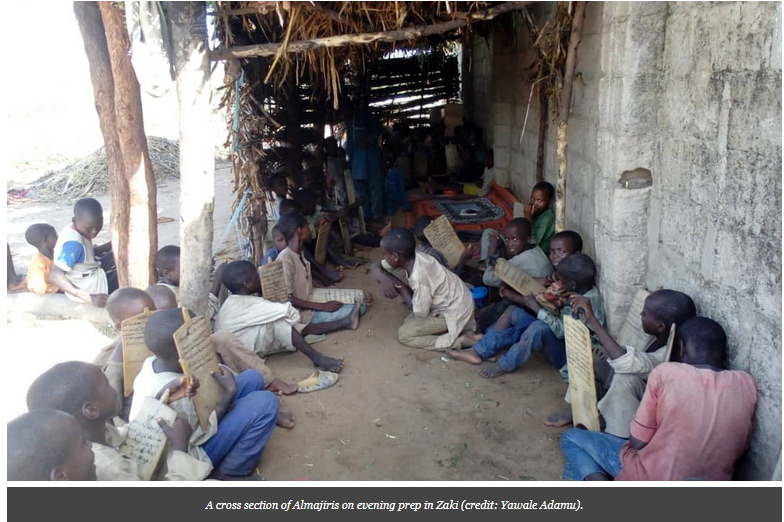

The Tsangaya schools are the open spaces where children are made to learn and recite the Qur’an.

Musa Abdullahi’s journey commenced at the tender age of six when his father entrusted him to the Tsangaya school with the intention of learning to recite the Qur’an.

However, he soon discovered an additional role thrust upon him—he was required to toil on local farms and submit his daily earnings to his teacher. At the home of his teacher, he was further subjected to extensive chores by his master’s wife. Relocating to Dambam along with his teacher just a year after his enrollment, Abdullahi’s existence has been marred by laborious work on farms, transferring his earnings to his teacher, and enduring the fear of brutal punishment for noncompliance. Farm proprietors even directly negotiate labour fees with his teacher, circumventing his consent and perpetuating his vulnerable state.

Musa’s experience mirrors Abdullahi’s fate. At the age of 15, this Almajiri child hails from Bachirawa, Kano State, and has undertaken domestic work to sustain himself. However, the fruits of his labour seldom reach him. Whenever he receives payment, his teacher, Malam Magaji Dambam, seizes the money for personal use within his family.

This recurring pattern of exploitation extends to the story of Musa as well. Under the guardianship of Malam Magaji Dambam, Musa has been subjugated to the role of a domestic servant, serving an Alhaji in Dambam. Despite being entitled to a monthly wage of N5,000, he has not received a single penny throughout the two years he has dedicated to this work.

In their young lives, these Almajiri children are bound by circumstances of hardship and mistreatment, thrust into labour against their wishes and left powerless to reclaim their rightful earnings.

“My hard-earned salary vanishes into my teacher’s hands every month. He cunningly receives the payment without my awareness, leaving me without a single penny from it,” Usman lamented.

Garin-Dawa’s ordeal is even more disheartening. A teenager from Kano, he was enrolled for Qur’anic studies under the guidance of Alarama Ibrahim Unguwar Katsalle in Zaki, Bauchi State. However, instead of imparting knowledge, this malam exploited his students by assigning them as farm labourers while he hoarded their wages for himself.

Annually, Garin-Dawa, along with over a hundred peers, journeys to Bauchi to seek paid labour on farms or within the city. Initially, their teacher facilitated this venture, but with time, he withdrew due to their growing familiarity with the surroundings. Despite infrequent visits, his sole purpose was to claim the meager earnings they generated. Upon returning to Zaki, Alarama Ibrahim promptly seizes every bit of their hard-earned money, leaving them burdened with suffering and despair.

Adding to the turmoil, the teacher’s wife also capitalizes on their labour, selling firewood sourced from the bush by Abubakar and his fellow Almajiris under her husband’s authority.

Despite dedicating five years to Alarama Ibrahim’s tutelage, Abubakar’s progress in memorizing the Quran remains minimal. Out of the 60 Hizb constituting a complete Quran, he has only managed to commit five Hizb to memory. Each Hizb contains 18 pages. This poignant situation reflects the challenges and struggles faced by these young learners who, despite their efforts, find themselves caught in a cycle of exploitation and deprivation.

All of them are victims of a weak regulatory system that failed to hold both Tsangaya teachers and parents to account in line with the provisions of a Bauchi State law prohibiting juveniles, children under the age of 18, from accompanying Qur’anic teachers.

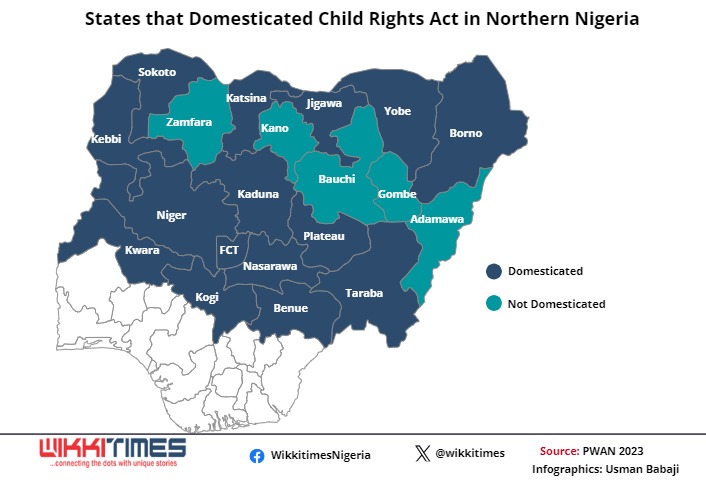

Similarly, the state is yet to domesticate the Child Rights Act. At the moment, the act only scaled first reading at the Bauchi State House of Assembly.

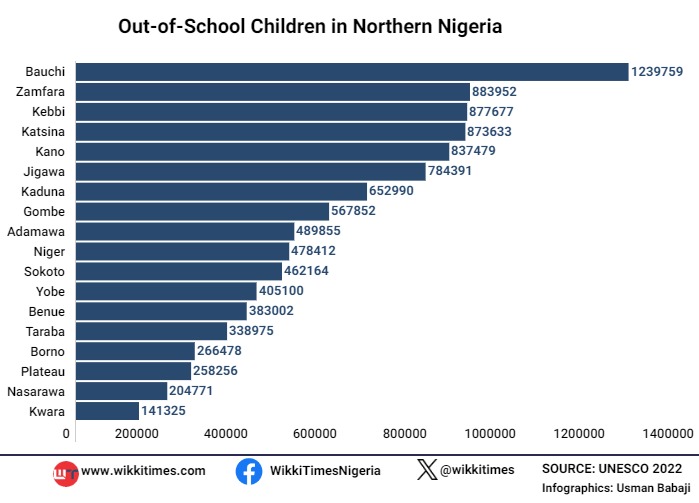

Data from UNICEF indicates that in Nigeria, about 10 million Almajiri children constitute 81 percent of the out-of-school children in the country while many parents, especially in the northern part of the country continue to send their children to Almajiri schools in fulfilment of their obligation to provide free religious and moral education to their children.

Similarly, data has shown that out of the 19 northern states, Bauchi accounts for the highest burden of out-of-school children with over 1.2 million children not attending formal BASIC education institutions.

What the Law Says

The law, Juveniles Accompanying Qur’anic Mallams (Tsangaya teachers) Prohibition Law CAP76 vol 2 of the 2001 edition of Laws of Bauchi State, outlawed movements of Almajiris from one place to another with or without their teacher. This movement is no different whether the parents of the children consented to it or not.

Section 3 (1-2) of the law prohibits either a Tsangaya teacher or parents or guardian of a child from seeking or giving out a child to any Almajiri teacher who moves around with such children under the guise of teaching and seeking Qur’anic education.

It states:

Any Qur’anic Mallam who removes a juvenile from the custody, care or charge of his parent, [or] guardian and moves with him from place to place anywhere in the state shall be guilty of an offence.

Any parent or guardian of a juvenile who gives out a juvenile under his custody, care or charge to Qur’anic Mallam and whom he knowingly will move from place to place with such juvenile or consents to such movement shall be guilty of an offence.

WikkiTimes learnt that based on the interpretation of the law, a juvenile is any person who has not attained 18 years of age.

Section 6 (1) empowers operatives of the Nigerian Police Force working in the state and traditional rulers to arrest any Qur’anic Mallam found wandering with Almajiris within the territorial enclaves of the state. It states that:

Without prejudice and in addition to the general powers of the police under the Police Act, it shall be the duty of every district head, village head, ward head and officer of the Social Welfare Division to arrest and or report to a police officer any Qur’anic Mallam found wandering with juveniles in his place of authority.

Similarly, section 6 (2) of the law gives power to every emir and chief in Bauchi to ensure that district, village and ward heads within his domain strictly perform the duties vested on them – enforce the provisions of this law in their respective communities.

Also, section 3 (3a-b) provides that any person who contravenes the provisions of this law shall on conviction be liable:

For a first offence to a fine of N500 or imprisonment of two years or to both such fine and imprisonment;

For a second or subsequent offence to a fine of N1000 or to imprisonment for a term of four years or to both such fine and imprisonment.

Barrister Interprets Bauchi’s Almajiri Law: Says Child Safety is still precarious in the state

Barrister SG Idrees, the Principal Partner of Al-Mufeed Law Firm, provided a comprehensive interpretation of the law in question. He said the law’s intention is to prohibit the practice of “nomad Qur’anic teaching and learning,” wherein Tsangya teachers transport children from one location to another, with or without parental consent.

Importantly, Barrister Idrees emphasized that the law does not aim to completely bar Qur’anic teachers but rather seeks to confine Tsangaya teachers to a specific and consistent environment. He highlighted that if a Qur’anic malam resides in a particular area, they should remain present there consistently, teaching the children without disruption.

Furthermore, Barrister Idrees underscored a critical concern: the potential for human trafficking due to the movement of these children across different places. He explained that when teachers transport children away from their familiar and safe surroundings, their security and freedom may be compromised. The law serves as a safeguard against such risks.

The legal expert also pointed out that the law empowers the government to effectively oversee the activities of Tsangaya school teachers. Allowing unrestricted movements, he argued, would hinder the authorities’ ability to monitor both the well-being of the children and the conduct of their teachers.

Barrister Idrees further emphasized the vulnerability of the children enrolled in Tsangaya schools, as many of them are under 18 years of age. He stressed that it is the government’s responsibility, along with other stakeholders, to provide them with the highest level of protection.

Concluding his analysis, Barrister Idrees clarified that although Qur’anic teachers are permitted to instruct within a specific scope, they are not expected to engage in constant movement that could hinder the government’s oversight of their activities. This interpretation sheds light on the rationale behind the law’s provisions, aimed at ensuring the safety, education, and proper monitoring of children in Tsangaya schools.

While advocating for compliance with the law, Barrister Idress said the law requires a review considering the offence and alternative commensurate fines encourage the commission of the offence.

He said other laws seek to regulate Tsangaya education in the state which ought to be harmonised. “If you look at this law you realise that it is not alone. You look at other legislations like Qur’anic Malam Registration Law and the Juveniles Accompanying Kuranic Malams Prohibition Law should be merged because there is no need to have several legislations dealing with the same subject matter.”

Bullying Among Almajiris

Among Almajiri children who have spent years devoted to memorizing the Qur’an under Tsangaya teachers, a troubling dynamic emerges where older individuals exploit their seniority to mistreat and even steal from their junior peers. While the Tsangaya educational setting acknowledges the concept of seniority, the lack of a formalized code to regulate the behaviour of senior Almajiris towards their junior counterparts has led to a significant imbalance of power. This situation has given rise to a near state of chaos, leaving many young Almajiris vulnerable to the actions of their older, potentially bullying colleagues.

Investigations by WikkiTimes reveal that within this environment, where an established hierarchy exists, senior Almajiris often engage in acts of physical and emotional aggression towards their junior counterparts. This unchecked behaviour creates an atmosphere of insecurity and victimization for the younger Almajiris, who are left defenceless against the actions of their more dominant peers.

It is evident that even the Tsangaya teachers, who themselves have grown up in a similar chaotic environment, do not actively intervene to curb the excesses of senior Almajiris. This inaction perpetuates an environment where the well-being and safety of younger Almajiris are disregarded, further amplifying the vulnerability of these children.

In essence, the absence of a structured system to manage the behaviour of senior Almajiris has contributed to an environment where bullying, intimidation, and the mistreatment of younger peers are prevalent. This situation not only undermines the sense of security within the Tsangaya setting but also hampers the overall quality of education and well-being of the junior Almajiri students.

Auwalu Gombe, a 7-year-old Almajiri who is under the guidance of Alaramma Isah in Dambam, faces a distressing ordeal. After tirelessly going door-to-door in search of food, Auwalu finds himself deprived of nourishment by his elder peers. Hunger becomes his nightly companion as he goes to bed on an empty stomach. He explains, “My seniors are shy to go round houses in the city begging for food because of their older age.” Despite his efforts, his seniors seize the food he collects and consume it in front of him, leaving him without a morsel.

Auwalu’s experience is shared by many junior Almajiri children within the Tsangaya system. These young learners are compelled to fend for themselves, as their teacher fails to provide them with regular meals. “Our teacher does not give us three square meals, meaning every Almajiri child must look for food to eat in the morning, afternoon, and evening,” laments Auwalu. Unfortunately, the seniors’ bullying behaviour goes unchecked, and their strength intimidates younger Almajiris into submission.

Senior Almajiris not only confiscate food from their junior counterparts but also subject them to cruel treatment, including physical abuse. Umaru Buba, a 10-year-old Almajiri, reveals, “I received a lot of torture from my seniors. At every slightest opportunity, they beat the hell out of me. I have no one to save me from their excesses, not even my teacher.” This culture of abuse extends to unwarranted corporal punishments, leaving junior Almajiris like Umaru vulnerable and defenceless.

In addition to food and physical abuse, the seniors’ dominance extends to forcibly seizing personal items such as soap, detergent, and other valuables from the junior Almajiris. These distressing accounts underscore the urgent need for systemic change and reform within the Tsangaya system, as the current conditions perpetuate a cycle of suffering and vulnerability for these young learners.

Disturbing Living Conditions

During its investigation, WikkiTimes conducted visits to several Tsangaya schools in Bauchi, revealing distressing conditions that are nothing short of alarming. The state of these institutions is a cause for concern, especially in the context of where the children retire for the night. The reporter discovered that numerous Almajiri children are forced to sleep in squalid environments, including dirty rooms within unfinished buildings, market stalls, and open spaces devoid of any protective measures. Unfortunately, these conditions expose them to the risk of infections due to their close proximity to mosquitoes, lice, and bedbugs.

One such example is Malam Malam Tsangaya school in Kesla, Misau local government area. Here, a shocking scene unfolds as more than 50 Almajiri children are cramped into a room and parlour mud house with a thatched roof. Inside these confined spaces, 25 Almajiris are squeezed together, lying on mats placed on dusty floors. This overcrowded and unsanitary arrangement further magnifies the plight of these young learners, who are subjected to substandard living conditions that seriously jeopardize their health and well-being.

The dire circumstances depicted within these Tsangaya schools underscore the urgent need for comprehensive reforms in the treatment and education of Almajiri children. These conditions not only hinder their learning but also perpetuate a cycle of vulnerability and neglect. It is imperative for authorities and stakeholders to address these issues promptly, ensuring that the dignity and rights of these children are upheld and that they are provided with safe, clean, and conducive learning environments.

WikkiTimes gathered that the room neither has a door nor windows to prevent mosquitoes and rodents from gaining access. And, this exposed the children to infections.

One of the Almajiris at the school, Abdulrahman Kesala said the mat given to him by his father has become spoilt because of rain since the place has no windows and doors. So he has to be sleeping on a cold dusty floor and he has fallen sick many times due to his unhygienic environment.

“When my father brought me here for admission, he openly asked me to never return home before my graduation. Despite the great discomfort tied to my stay, I never attempted to flee back home because my father would forcefully take me back to the school,” he said.

Mustapha Takadinga who schooled at Tsangayar Malam Dahe located at Alimri, Misau said he parted ways with comfortable sleep following his admission into the school. Apart from being too dirty, Mustapha’s room gives a very nauseating smell because most of his colleagues bedwet.

“Our room is stinky and unhygienic,” he lamented.

Malam Ibrahim Sidi, a Tsangaya teacher formerly based in Giade told WikkiTimes that the lack of a befitting facility that can house 50 Almajiris enrolled on his school, forced him to migrate to Katagum with the children.

However, years after settling in Katagum, Sidi only put up three shanty rooms used by his Almajirs as shelter. “The Almajiris squat in the three rooms,” he insisted.

The three rooms are roofed with thatch that leaks water during raining season. And because the rooms are often overcrowded and hot, the children often sleep outside on bare ground at night under the bright moon.

“You can find as many as 20 Almajiris in a single room. They sleep outside around the period we used to record excessive heat,” he said.

Despite his inability to provide decent accommodation, Malam Sidi continues to lure more prospective Almajiris into his fold. He said, “My main challenge is an inadequate structure that can properly shelter the students.”

How Tsangaya Teachers Impose Levy On Almajiris

Tsangaya teachers in Bauchi imposed a weekly levy on the Almajiris under their custody. The teachers enforced collection with punitive measures against defaulters who are jobless. Levy defaulters receive lashes, abuses and insults from their teachers.

The amount collected is relative to the location and calibre of the Tsangaya teacher. According to the Almajiris interviewed, Tsangaya teachers in Dambam and Zaki collect an average of collect N30 weekly per head, in Misau it varies between N50 to N100.

WikkiTimes’ investigation has uncovered that the responsibility of making these payments does not fall upon the parents or guardians of the Almajiris. Instead, it is obligatory for every child to contribute. The collected levy finds its way into the pockets of the teachers who frequently allocate it for personal and familial purposes.

Idi Musa Didaye, an Almajiri based in Dambam, shared that his teacher, Malam Isah, ensures that he administers lashes to every child who fails to provide the N30 weekly fee. Didaye recounted that following the punishment, the teacher issued a warning for the students to bring the money the following week, or else more lashes would be inflicted for non-compliance.

“My father neither sends a single coin to me nor to the teacher concerning the weekly dues. On many occasions, I’m left to manage on my own. I dread Wednesdays because it’s the day the weekly collection is due. Whenever I am unable to gather N30, fear grips me,” he expressed.

Shehu Musa, a frail-looking Almajiri from Tsangayar Malam Dahe Alimri in Misau, shared with WikkiTimes that he pays N50 every week to his teacher. He stated, “He does not spend the money on our welfare. Instead, he uses it to meet the daily needs of his household.”

He added, “Senior Almajiris pay N100 per week. Defaulters of the weekly payment received several strokes of canes from the teacher himself.”

Tsangaya teachers, who spoke with WikkiTimes, confirmed their practice of collecting a weekly levy from their students. Malam Alhassan Adamu, a Tsangaya teacher, mentioned that he sends out his Almajiris to earn money. He explained, “Except for one day in a week when whatever the students make belongs to me, money collected any other days belongs to them,” he stated with a sense of entitlement.

At Mala Adamu’s school, each Almajiri is fully responsible for their own sanitation and hygiene. They purchase soap, detergent, and other materials for personal upkeep, often seeking jobs as farm labourers or domestic help. “My students work on my farms to help me cultivate crops to feed my family and relatives,” he explained.

Malam Adamu, whose Almajiris come from Bauchi, Jigawa, Gombe, and Yobe, confirmed to WikkiTimes that he freely moves around with them without facing any restrictions from authorities. He travels with them within Bauchi state and neighbouring states throughout the year. The only challenge he routinely encounters is exorbitant transportation costs, not the fear of being arrested by the police for trafficking Almajiris. He said, “I move around unhindered during rainy and dry seasons without any authorities restricting my movements. For instance, this year, I took them to Hadejia where they do things like shoe shining, selling water, dry cleaning, and petty jobs. By the time they return, they give us the money raised.”

Malam Idris Abdullahi Gamawa, a Qur’anic teacher in Zaki, also receives proceeds from the labour of the Almajiris children under his care. Malam Gamawa, who previously travelled with his Almajiris, now sends them to neighbouring states in search of opportunities. He said, “I sent some of my Almajiris to other parts of Bauchi and beyond. I expected them to come back after harvest. Their proceeds enable me to feed my family. We sell some parts of it as well. The money is useful to both of us.”

Police Defend Enforcement of Almajiri Law, Despite Lack of Arrests

The Bauchi State Police Command has defended its role in enforcing the provisions of the Bauchi State Juveniles Accompanying Qur’anic Malams law, asserting that only courts possess the authority to sanction infringements. However, despite 38 years having passed since the law’s enactment, the police have been unable to confirm the arrest of any Qur’anic Mallam or parents who have violated the law.

SP Ahmed Mohammed Wakil, the Bauchi State Police Spokesperson (PPRO), emphasized that Almajiri children are vulnerable and susceptible to various forms of exploitation under the guise of pursuing religious education. He explained that all reported cases involving Almajiris are thoroughly investigated and brought before the courts for resolution. The law empowers the courts to provide safe and habitable conditions for the juveniles (Almajiri) after their respective Malams have been indicted and convicted of alleged offences.

Wakil affirmed the police force’s commitment to combating criminal activities, such as trafficking, cruelty, child labour, and servitude, and underscored that the law has facilitated appropriate sanctions for convicted offenders. He acknowledged the gradual nature of law implementation and expressed readiness to address challenges as they arise.

WikkiTimes’ efforts to gather information about the law’s implementation from the Bauchi State Ministry of Justice, the primary executor of the law, were met with difficulties. Despite attempts to arrange an interview with the Permanent Secretary of the ministry, Aliyu Ibn Idris, no response was received to calls and messages until a subsequent visit was made.

Ibn Idris, upon contact, initially denied the existence of a law prohibiting juveniles from accompanying Qur’anic Mallams in Bauchi State. However, upon being provided with reference details of the law, he promised further investigation but failed to follow up on the promise. When he called back on 26th July at about 2:22 p.m, He argued that Bauchi State does not have a law prohibiting juveniles from accompanying Qur’anic mallams. However, after this reporter provided him with reference details of the law, the Permanent Secretary promised to call back again after completing his findings but never did as at press time.

The situation highlights a potential gap between the implementation of the law and the on-the-ground realities faced by Almajiri children in Bauchi state.

This investigation is produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Center for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development Inclusivity and Accountability Project (CMEDIA) and funded by MacArthur Foundation.