Sangaya is a vital institution that has provided Quranic education and other spheres of Islamic knowledge for over a millennium in this region. Its existence predates the Saifuwa dynasty, extending through the first and second Kanuri empires, the Kanem-Borno Empire, colonial Borno, post-colonial Borno, and into the present day. Borno’s historical and international prominence as a cradle of civilisation in Africa is deeply intertwined with the Sangaya institution.

Throughout these eras, Sangaya played an instrumental role in manpower training that serviced various facets of governance, including administration, international trade, diplomacy, socio-economic development, politics, defence, and security. The term “Sangaya” became synonymous with prestige, representing a status aspired to by generations. This was not only due to its religious significance but also because it was a cornerstone of self-actualisation. In fact, even the Mais (Kings) of the time were required to master the Holy Quran and other aspects of Islamic jurisprudence before they could be considered for succession to the throne. Likewise, Kingmakers, the Chief of Defense Staff (Mai Nyi Kenindimi), and his commanders, as well as other high-ranking officials such as the Prime Ministers (Waziri), Ministers, District Heads, Village Heads, and Ambassadors, were all expected to have attended Sangaya. The head of a Sangaya is known as Ba’a Goni, who serves as the spiritual leader of their respective communities. Ba’a Gonis play crucial roles as guides and advisors to political leaders at various levels. They preside over wedding ceremonies, naming ceremonies, and funerals. Additionally, they serve as consultants to the sick, hosts to strangers, mediators in conflicts, and representatives of popular opinion within their communities.

The recognition and acceptance of Ba’a Gonis’ roles and functions within the community made it imperative for ruling dynasties to appoint some of them as Shettimas, who acted as advisors to the kings. These Gonis, in turn, liaised with other Gonis, playing a significant role in maintaining law and order throughout Borno’s history. Thus, the head of Sangaya, the Sangaya institution itself, its pupils (Fugura/Fuwura/Huwura), and its students (Maajir) have all been highly esteemed as key elements in actualising social status and political recognition, aside from their all-encompassing religious significance throughout the history of the Kanuri people and northern Nigeria as a whole.

The concept of Sangaya

The term “Sangaya” originates from words associated with light, such as “dune of ashes” (ashes accumulated from spent fuel used for lighting during the night) or “Ngaya” (a piece of broken pottery used for grinding charcoal, a vital ingredient in producing ink). Regardless of the term’s exact origin, it is evident that it captures the relationship between light – an essential component of understanding – and knowledge. Whether it refers to the light that enables students to read their tablets (Allo) or books or the context of an ink and pen factory, the term points towards enlightenment. The saying “knowledge is power” finds its prominence in the Western Sudan Empire, where Sangaya emerged as a system of learning, with its success measured by its contribution to society and the community.

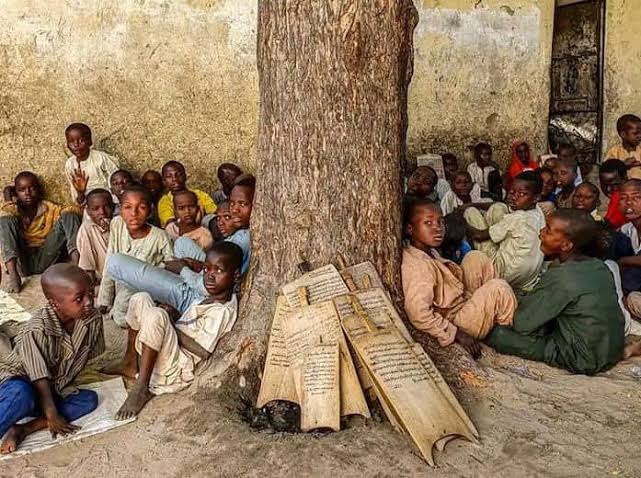

Sangaya, as a term, connotes a centre of learning widely recognised throughout pre-colonial Western Sudan empires, notably in Borno. Sangaya is a formal educational system with a curriculum and scheme of work similar to those found in Western-modelled educational institutions, though differing in structural arrangements. Sangaya is synonymous with enlightenment, knowledge, and wisdom. It attracted people from across North, West, and Central Africa, serving as a melting pot of civilisations that bolstered the hegemony of the Kanuri empires throughout pre-colonial Africa.

The nature of Sangaya operations

The operational nature of Sangaya is unique in many respects, from its entry requirements and admissions processes to its training, graduation, and postgraduate programmes, including up to the professorial level.

Entry requirements are religious in nature, with admission conditioned upon professing the Islamic faith. This automatically qualifies an individual for enrolment, motivated by the desire to encapsulate in the Holy Quran, which makes it incumbent upon every Muslim to learn how to recite, understand, and translate the Holy Quran, with memorisation of the entire scripture being a possibility.

Admissions are based on trust, with individuals admitted irrespective of race, region, ethnicity, or tribe to learn the basics of Islam, particularly the recitation of the Holy Quran. Pupils and students are classified based on their learning abilities. Traditionally, those in the nursery category are allowed to attend to familiarise themselves with the environment before being formally recognised. Formal admissions typically occur around the ages of six to seven, with verbal registration based on trust. Parents express their commitment by saying, “Fujiya Cipne, Nuyya Rumne” (cure him when he falls sick and bury him if he dies). The father, not the mother, accompanies the child, and since most are boarding pupils, the separation is often emotional.

At the beginner level, pupils are taught the last ten chapters of the Holy Quran, starting with the opening Surah Al-Fatiha, known in Kanuri as “Alamtara wa Nasi.” Upon completing these portions, the pupil is given a wooden tablet (Allo). Thereupon, he or she begins learning the alphabet, pronunciation, word formation, and phonology, which lead to the development of writing skills. They then proceed to write the verses they have learned, reciting them until memorisation is complete. This process continues until they can write up to ten verses, progressing through ‘Summun’ (one-eighth of the Qur’an), ‘Rubbu’ (one quarter of the Qur’an), ‘Nussub’ (a half of the Qur’an), and ‘Issub’ (one of the sixty parts into which the Qur’an is divided).

At this stage, they prepare for the secondary level, where they can write their portions and exchange corrections among themselves, before presenting them to the head of the Sangaya. Upon completion, they scout for an area or community where they can be invited for a graduation ceremony known as ‘Zuwu Faral’. This event marks the climax of competition, as they are now in adolescence, with each student striving to avoid mistakes. A single error can be embarrassing not only to the student but to the entire Sangaya. It is akin to an intellectual competition. Such efforts can lead to their graduation.

The importance of the Holy Qur’an and Islamic jurisprudence, as well as their esteemed social status, motivates some to continue their studies even after graduation. This stage is referred to as ‘Duwallo’, where they repetitively follow through the memorisation of the holy book. While postgraduate students are engaged in their duwallo, they also pursue other activities such as learning other branches of knowledge, especially Fiqh, Tawheed, and Hadith, all of which are anchored in Qur’anic knowledge. Simultaneously, the postgraduates engage in crafts like cap knitting (Zawa Duto), attire embroidery (Fukka Pita), hawking, farming, and even petty trading.

At this transitional stage, some continue their scholarship to the highest level, becoming a Goni, while others become full-time artisans, farmers, international traders, and scribes to administrative bodies, clerks, and registrars in the courts.

Characteristics of the Sangaya system

The Sangaya institution is characterised by a single structure that is divided into sections. Each section accommodates a specific level: beginning, middle, and advanced. Each of these sections is supervised by advanced students under the close guidance of the head of Sangaya.

Intelligent, trusted, and certified graduates often take some pupils and students, including the children of the head of Sangaya, to a distant community called ‘Dierea Kurayae’ (intellectual sojourn). This enhances their teaching career as it serves as a venue to actualise and perfect classroom control and management, as well as learning how to live with strangers. During their primary assignment, the Maajir (Graduate) is also given an introductory letter from the head of his Sangaya to the host head of Sangaya, which allows him to attend conferences and seminars (Darasu and Massaba) and study other branches of Islamic education like Fiqh, Tawheed, and Hadith.

These conferences sharpen individual abilities in a competitive form, often culminating in the recitation of the entire Qur’an from memory, thereby becoming a Hafizul Qur’an (memoriser of the Qur’an), a position highly coveted by all – a supreme gift that a human being can attain in this world.

Sponsorship of academic journeys in the Sangaya system

Who, then, is responsible for sponsoring these academic journeys? The answer to this question forms the basic characteristics of Sangaya, which is founded on imparting Qur’anic knowledge – a primary source of Islam that every Muslim aspires to learn. Thus, the responsibility of Sangaya education largely depends on communal goodwill in the following ways:

Firstly, the Sayinna or Ba’a Goni is the Imam, the spiritual head of the community, where Zakkat (butu) is collected. This gesture helps alleviate the burden on the Gonis, who are teaching religious obligations on behalf of the parents, as it is their job, occupation, and profession. With this material support, they can take care of their families and students. Secondly, the pupils and students often assist in agricultural production to boost their food security while at the same time the parents of these students send material support to where their children are studying.

Thirdly, in a very large Sangaya where there is insufficient food, the pupils and students often go out in search of food from house to house at periodic intervals. Fourthly, the pupils, students, and sometimes the entire Sangaya are contracted to perform spiritual duties, such as recitation and special competitions, which may reward them with a bull, ram, or even a chicken to celebrate. The pupils, students, and teachers in that institution often receive second-hand clothes, and sometimes even brand-new garments.

These factors constitute the basic characteristics of people separated from their parents for the sake of Islam, who might not even return to where they came from, instead establishing another school to propagate the teachings of the Qur’an. For example, if one were to trace the roots of each clan or tribe in Borno, one would be astonished at the origins of some tribes and people. At the same time, many Kanuris in the diaspora, residing in Hausa, Yoruba, Nupe, Tiv, Jukun, and other lands in Nigeria and across Africa, serve as a testament to the prestige of the Sangaya institution.

Challenges of the Sangaya system

This institution faces many challenges arising from the introduction and adoption of Western education as the model for governance. These challenges place the institution and its products at a strategic disadvantage. The institution has been relegated to the traditional institution, which itself is struggling for survival. However, since Sangaya is obligatory for every Muslim, it continues to thrive under various circumstances, adapting to the challenges of each phase.

The institution began to wane when primary schools adapted curricula on Arabic and Islamic knowledge, as well as the emergence of Arabic Teachers Colleges and other Islamic-related institutions by the government to provide the labour needs of the state. In either case, the size of these schools does not match the level of demand, so the Sangaya continues to flourish. Presently, there exists a sort of modernised Sangaya recognised by the government, but they are too few to cater to the demand. In each primary school, there are Islamiyya schools, which have led to the proliferation of Islamiyya secondary schools with certificates that qualify students for tertiary institutions, which also fall short of the demand. In terms of mastery of the Holy Qur’an, Fiqh, Tawheed, Hadith, and other spheres of Islamic jurisprudence, Sangaya’s impact is unchallenged. The professors referred to as Ba’a Gonis are the true ‘gurus’ in all matters. On that note, I would like to draw the government’s attention to the ongoing proposal to modernise Sangaya, urging caution and ensuring the involvement of Baba Gonis.

Prospects of the Sangaya system in contemporary Nigeria

The prospect of Sangaya revolves around the primary source of Islam. Without it, it is impossible for Muslims to master the religion, and thus, Sangaya responds to changes in various circumstances. It will continue to thrive as long as Islam remains a universal religion. Most modern Sangayas have successfully combined Qur’anic education with Western education, producing students and graduates with both Islamic and Western knowledge.

We continue to appeal to the government to consider including Sangaya products (i.e., students/graduates) in its skill acquisition programmes and other projects that would provide a sense of belonging to these students. These products do not aspire to be employed by the government due to their background; instead, they tend to be independent and self-employed in various activities like trading, farming, carpentry, brickmaking, sewing, artisanal work, and other means of livelihood, thereby becoming employers of labour rather than a burden on the government.

Finally, the Sangaya system is a voluntary educational institution that survives on the goodwill of the people, which over time has positively influenced the socio-economic and political development of Nigeria. It is synonymous with religious responsibility, a social status aspired to by every Muslim, but it has been relegated by successive policymakers in the comprehensive structuring of the system for proper integration to cope with modernity. The West, and indeed the world, have already recognised the contribution of Sangaya, but how can we carry it along to integrate it to serve the needs of contemporary challenges, considering the evolving culture of individualism? I hope this and other questions could open up debates for responsible and responsive government and non-governmental organisations on how best to sustain such prestigious institutions.

Recommendations for integrating the Sangaya schooling system into the Western education system in Northern Nigeria.

The Sangaya schooling system, deeply rooted in Islamic tradition, has played a significant role in the educational and cultural fabric of northern Nigeria, particularly in the Lake Chad region of Borno and Yobe States. However, the increasing need to modernise education to meet contemporary demands necessitates a strategic integration of the Sangaya system with the Western education framework. This integration, if carefully planned and executed, could enhance educational outcomes while preserving the rich cultural and religious heritage of the region.